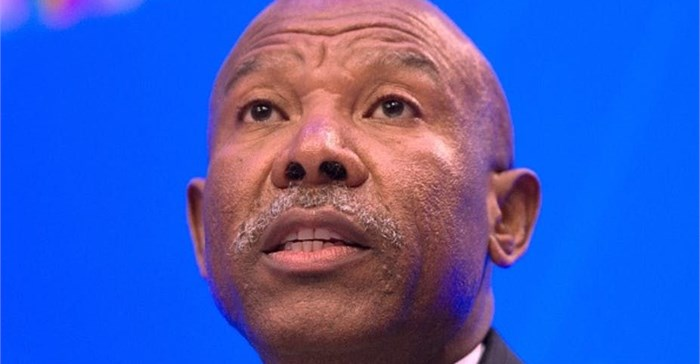

In conversation with South Africa's central bank governor Lesetja Kganyago

- Milllenia

- Aug 31, 2021

- 6 min read

The South African Reserve Bank is critical in formulating and implementing monetary policy and ensuring financial stability in the country. In this Wits Business School Leadership Dialogue, Professor Mills Soko talks to Reserve Bank governor Lesetja Kganyago about the central bank and the issues that it grapples with on a day-to-day basis.

Mills Soko: When you were appointed as governor one of the first things you did was to go to your village and you went on a shopping spree. What was the significance of this gesture?

Lesetja Kganyago: I felt it was an opportunity to teach people about the value of money. And I went back to the same shop, where every morning I would go and buy bread before going to school. There was an important inflation lesson because at the time – 1972 – a loaf of bread cost 10 cents. And I was saying to the villagers, today you cannot get a loaf of bread for 10 cents. You cannot even get it for R10 but the size of the bread is still the same. I said to them, therein lies the lesson of inflation, and that’s the reason why we have to keep inflation in check. I think the message got through to them.

Mills Soko: Are there any differences between the mandate of the South African Reserve Bank and other central banks in the world?

Lesetja Kganyago: Central banks are creatures of their society. Society creates institutions and gives them a particular responsibility. The one thing common across central banks is that they have a responsibility for price stability.

The authors of our constitution were of the view that price stability is not an end in itself. It is a prerequisite for balanced and sustainable growth. South Africa’s constitution goes even further. It says the central bank can also do such other things, ordinarily done by other central banks, provided they are spelled out in national legislation.

The bank is also responsible for financial stability, outlined in the Financial Sector Regulation Act, and the country’s payments system, enabled by the National Payment Systems Act.

Mills Soko: Why is the focus limited to price stability? Why not focus on unemployment?

Lesetja Kganyago: We need balanced and sustainable growth. Price stability is a necessary condition for that growth. But it is by no way a sufficient condition.

It is important to distinguish between two important aspects. Monetary policy can only affect what is called cyclical growth. It will not affect structural growth. The monetary policy horizon is 12 to 18 months. So, monetary policy can only affect short run growth.

Job creation is an outcome of sustained economic growth. For that to happen, all players in the economy have to work together to achieve that.

I have a friend who explains this using the metaphor of the speed limit on the road. If you drive faster than the speed limit, the chances are that you could even lose your life or very soon have an appointment with the courts because you have broken the speed limit. If you drive below the speed limit, the chances are that you will reach your destination later than you would have otherwise.

Central banks are better able to influence cyclical or short-run growth.

The central bank is not going to create that higher growth rate that we require on its own. There is nothing monetary policy can do to produce the engineers that the country needs in order for its economy to grow. This is but one example.

Mills Soko: How does the Monetary Policy Committee of the bank function?

Lesetja Kganyago: It comprises the governor and the three deputy governors. They then add a staff member or two. Currently we have the chief economist, and they make up the Monetary Policy Committee.

The model that we use for forecasting, like all economics models, does have assumptions. And so the process starts with the Monetary Policy Committee members meeting with the Economic Research Department to agree on what the assumptions for the forecast are going to be. The two most important assumptions have to do with the price of oil and the exchange rate. They are important because they influence what is going to happen to inflation and what happens to economic growth.

Once we have signed off on the assumptions, the Bank’s modelling team puts together a forecast of what they think economic growth is going to be, what inflation is going to be.

The Monetary Policy Committee will then meet with a number of officials over three days. On the first day we assess the state of the economy, starting with the global economic outlook, moving to the domestic economy, and then we look at global and domestic financial markets respectively. On the second day, a smaller group debates the forecast.

On the third day, the chief economist will outline the options and gives the reasons why we should keep interest rates the same, why we should hike or cut them.

Each committee member will then say what their preference is.

If there is disagreement, we will debate and debate and debate some more. If we can’t convince each other, we go with the preferences of the majority of the committee. Once that is done, the chief economist drafts the statement, which is sent to all members. The committee then debates every single word, and where every comma should be. And by that time you realise that your English is more important than your economics.

Mills Soko: Your thoughts on a cryptocurrency?

Lesetja Kganyago: It is a crypto asset. A currency must meet the following three criteria. One, it must be a generally acceptable medium of exchange. Secondly, it must be accepted as a store of value. And thirdly, it must be a unit of a account. A cryptocurrency is a store of value. It is a medium of exchange, but is not generally accepted. It’s only accepted by those who are participating in it.

Our approach is that we are going to have to regulate this because people go and invest in cryptos and when they lose money, they ask what government has done about it.

Many of these crypto assets have got a technology called blockchain that underlies them. It can be useful in many other respects. And so, like many other central banks, we are experimenting with the blockchain technology.

Mills Soko: Are there any plans to regulate financial technology (fintech) firms in the same way as banks are regulated?

Lesetja Kganyago: We don’t intend to regulate fintech firms like banks. But if it walks and quacks like a duck, then it is a duck. So, if you are a fintech firm, and you take deposits, we will regulate you like a deposit taker. If you are a fintech firm, and you do money transmission, we will regulate you like a payments provider. If you are a fintech firm, and you sell insurance policies, we will regulate you like an insurer.

Our regulatory mandate is to regulate activity.

It’s important that we understand the value that the fintech firms bring to the financial sector. We have created an innovation hub at the Reserve Bank in response to the growth in this area.

Mills Soko: Central bank governors have been criticised for being a bunch of unelected bureaucrats who make decisions without being held accountable. What is your response?

Lesetja Kganyago: Central bankers are unelected. Yes, we are technocrats. Yes, we have got a lot of power. One author called it unelected power.

I don’t think that we should have elected central bankers. I think it will defeat the purpose because instead of focusing on the task at hand, they will focus on the next election.

Central banking was given to technocrats whose job is to make the difficult decisions. But across the globe the power of the technocrats is constrained. There are parameters. And within these, central bankers must act independently, without fear or favour. In our case, this is prescribed in the South African constitution.

The other side of preserving independence is accountability. We have got to be accountable for the decisions we make, and the way in which we make those decisions.

We account to parliament. We also account to the public through our own public forums. The decisions we make are transparent and in the public domain, and thus open to public scrutiny.

This is an excerpt of the Wits Business School Leadership Dialogue. The full interview is available here.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments